THE SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA EXPLODING INEVITABLE

by Cole Coonce

There is a philosophy of the world that states that there is a common realization about the interconnectivity of all things physical and spiritual—that there is a unity at a profound level—and that our actions have somewhat infinite repercussions. This discipline is known as Zen. In the mid-1960s, it was a philosophy that was integral to the machinations of an offbeat trio of Nitro Bums from the west side of Los Angeles: Bob Skinner, Tom Jobe and Mike Sorokin, aka “The Surfers.” It defined their approach to the application of nitromethane vis-à-vis compression ratios and blower speeds. It defined who they were as individuals.

This is the story of how these three men stood the World of Drag Racing on its ear via their theoretical approach to life as applied to a Top Fuel dragster. It is the parable of two abstract yet linear thinkers, Skinner and Jobe, and their driver, Sorokin, and how they discovered that the path to Drag City and the trophy queen was also the path to nirvana and enlightenment.

It all began just a few lunar cycles before Baba Ram Dass coined the phrase “Be Here Now,” but this chestnut of wisdom could have been The Surfers’ mantra. For these shrewd and mischievous nitromaniacs, the drag strips of Southern California were a blank slate to gingerly project their desires and sensibilities in much the same way a Zen Master approaches the mysteries of life: Head First. With No Rear View Mirrors. This was not just about merely kissing a trophy queen on Saturday night. This was an exercise in all things theoretical and philosophical. It was an exercise in consciousness expansion. It was a journey.

And it was the ideal time to catch a wave, so to speak. The opportunity to express one’s self in the State of California then was as wide open and infinite as the blue waters of the Pacific Ocean. The only limits were one’s resourcefulness and ingenuity… And for approximately three revolutions around the sun it was absolutely high tide for the collaboration between Bob Skinner, Tom Jobe and Mike Sorokin. The Surfers ruled.

Although The Surfers made the universe shudder with their unique approach to both Top Fuel racing and, uhh, life itself, the genesis of their racing endeavors was much more prosaic than you would imagine. Its germination was in the days of Ozzy & Harriet and Googie Hamburger Stand Americana and it specifically took root on the corner of Jefferson & Sepulveda in Culver City, California. There stood a burger joint known as the “Nineteen.” Named eponymously after its nineteen-cent hamburgers, it was the epicenter for Cafe Society as interpreted by street-racin’ Southern California hot rodders. And its atmosphere, vibrations and “extracurricular activities” resonated deep in the soul of Mike Sorokin, at the time a lead-footed Venice High School student.

“The thing about the Nineteen was, not only did they have cheap food,” recalls local digger driver and one-time street racer Ron Hier, “they had a great big parking lot. We used to hang out there because we used to street race and ‘Sork’ was one of the guys who hung out there.

“When we first started hanging out with Sorokin at the 19,” Hier continues, “there really weren’t any drag strips—except for one all the way out in Santa Ana, and there were no freeways in those days. It was Gene Adams, Craig Breedlove and his ‘34, Leonard Harris, Mickey Brown, John Peters. What got Sorokin into racing was hanging out at the 19 and street racing with the guys.” After describing a crash “near the railroad tracks” involving a now-mega-famous race car driver (who shall remain nameless) Hier concludes that, “I can’t believe none of us got put in jail.”

Hier, who sold Sorokin a ‘34 Ford that was used to drag down Sepulveda Boulevard, mentions that Sork’s desire to race led to an ego battle with his old man, a conflict stereotypical of the era’s teenage rebellion. “His dad did NOT like drag racing… he didn’t like street racing, he didn’t like drag racing, he did not want Mike driving. He would come over and try and talk all of us out of racing.” Suffice it to say, the elder Sorokin’s pleas were the proverbial fallen tree and the “fast crowd” at the Nineteen was its empty forest. Ben Sorokin’s admonishments fell on deaf ears, mostly because he couldn’t be heard over the roar of un-muffled internal combustion engines and squealing tires as they roared down Lincoln Boulevard.

Simultaneous to “Sork” sharpening his reflexes on the malt shop circuit as well as in gas coupes and a D/Fuel dragster on the strip, Santa Monica City College students Bob Skinner and Tom Jobe began tinkering mischievously in academia with what, in essence, was the pursuit of a double major of chemical prankster-ism and the theory and application of nitromethane. And as the drag strips and the freeways experienced their concurrent boom, these two whiz-kid brainiacs pooled their brainpower with a local construction worker and schemed together on running a Top Fuel car out of a motel garage. It was the perfect opportunity to apply their studies to the real world…

“Skinner and Jobe, when they put the car together,” Hier recalls with bemusement, “…it was just a hare-brained idea.” Bob Skinner doesn’t dispute Hier’s assessment. “I had dabbled in street racing. I briefly ran a B or C/Gas car,” he recalls. “I had just got back from a three-month vacation and Tom Jobe and Jim Crosser said to me, ‘Okay, we want to build a fuel car.’ And I just said, ‘Okay.’ Most things that I have done along the way have been sort of spontaneous impulse without a lot of thinking about it. So when I came back and they said, ‘We want to build this car,’ I just said ‘Great’ and we just kind of got into it.”

Hier remembers how the team raised its venture capital: “Skinner and Jobe got together with Bob Skinner’s mother—who owned the Red Apple Motel there on Wilshire Boulevard in Santa Monica—and got her to sign for a ‘furniture loan’ for something like $5000.” Skinner and Jobe immediately cashed the check for the non-existent “furniture” and began gathering parts and pieces for their AA/Fuel Dragster, which was kept in a spare garage at the Red Apple.

Jobe sums up their rationale for running a Top Fuel dragster out of his Mom’s motel’s garage thusly: “It was a time when anybody could participate. When we started all we had was enthusiasm. We didn’t know nuthin’. We were just a bunch of street racers from Santa Monica,” he says. “My brother raced in a stock class with a Chevy and I was his motor man. He street raced six days a week and would go to the drags on Saturday night, but we just got tired of the ‘class’ deal. He won the Winternationals in ‘60 and runner-upped at the US Nationals, but he was always getting torn down and all that crap. We all kinda’ dabbled with C/Gas Willys and Mike drove a (C/Altered) roadster coupe with George Bacilek,” he remembers. “Anyway, all of us had messed with different classes and we finally said: ‘Classes? That sucks! Let’s build a dragster,’ but we didn’t know how to build one, you know.”

In other words, the only “competitor class” where Skinner and Jobe could dwell as free-thinkers was a class whose framework had no real… framework. Top Fuel.

So Skinner and Jobe began tugging on the shop apron strings of the local chassis builders and fabricators like a pair of hyperactive nephews that forgot to take their Ritalin. “There were a lot of (dragster) guys around here,” Jobe notes. “Every day after work we’d hit all the garages—there was a bunch of them in Mar Vista—we’d go to every one of them and ask some questions ‘til they’d throw us out and then we’d go down to the next one. We (finally) found out enough stuff because we had to build the whole thing ourselves; we didn’t have any money to buy anything.”

They might have been strapped for cash, but Skinner and Jobe were loaded with an intellectual camaraderie that couldn’t be bought. “Tom and I had a great ability to work together,” Skinner acknowledges in references to the sculpting of their short, scruffy, minimalist dragster. But their other colleague had a somewhat less theoretical take on drag racing and according to Jobe, “Our other partner just dropped out soon after we got the thing running.”

But just getting their homemade dragster running, nay just getting the digger to fire was an excruciatingly painful learning curve, according to SoCal drag-racing fixture Tom Hunnicutt, who was crewing for his friend Jim Boyd’s Red Turkey AA/Fuel Dragster the day The Surfers unveiled their creation at Lions Drag Strip in early 1964.

Hunnicutt says of that afternoon, “They kept pushing up and down trying to get the car to fire and it wouldn’t fire,” he laughs. “I don’t know if they had the magneto in wrong or what, but they kept pushing it on the return road for a long time—it wasn’t just once. It was a bunch of laps.” About this initial impression, Hunnicutt recalls thinking derisively, “‘These guys aren’t drag racers, who are they?’ They were kinda’ geeky.”

This is the phase where Skinner and Jobe were fine-tuning the chemistry of all things material and physical—and enduring the scorn of their opponents because their homemade, homely digger was a real back-marker. Even if they could get the motor to fire, part of the boys’ dilemma was that they had yet to settle on a driver who could viscerally and intuitively interpret their cerebral approach to Top Fuel racing and run it through the lights with the butterflies horizontal. Before Skinner and Jobe ultimately settled on Sorokin to shoe, there were a litany of drivers who attempted to hang ten in the cockpit, including “Lotus John” Morton, a journeyman sports-car racer who was sweeping the floor at Carrol Shelby’s place of employ (where Skinner also punched a clock). Morton, who had a reputation as being absolutely fearless and could handle any piece of machinery that had a throttle, describes his one-day tenure as shoe of The Surfers AA/Fuel dragster this way:

“The dragster ride happened when I was at Shelby’s,” Morton states in a passage from his biography, The Stainless Steel Carrot. “I got in the car at the strip. Really got packed in. I was sitting there in that thing thinking, I have really got myself into something. Here I was a sports car racer and had never driven anything down a drag strip before, not even my dad’s car, and I was about to drive the fastest thing they made. I was scared shitless. The thing was so powerful the centrifugal force of the clutch was trying to push itself out. I revved the engine and the sound ripped out like an explosion. My whole leg was trembling on the clutch.

“I let it out. Everything was a blur, the whole world went fuzzy. I let off for a second, just a tiny bit, and got pissed off at myself and floored it again. On my other runs I never let off but it didn’t matter; the thing was so fast I did a hundred and eighty my first run and that was it, never any faster. I put the clutch in at the end of the run and waited for the thing to stop. By the time it did, I could feel my leg was still shaking, like a dog shitting razor blades. But I did it. Something made me do it.”

Morton’s eloquent and punchy account reveals something about the state of The Surfers’ racing effort: For a couple of geeks, all of a sudden Skinner and Jobe were making beaucoup horsepower. But they lacked the final piece to their puzzle: A driver who could harness all that horsepower and ride the bulbous, minimalist machine bareback. And then Sorokin passed Skinner’s reflex test of catching a series of falling coins, hopped in the saddle and history was about to be capsized.

According to Skinner, “It’s hard to say how it all evolved because we had (Bob) Muravez driving and we had Roy Tuller driving, then ‘Lotus John’ drove, then we had Mike driving for us and we got rid of him and had other drivers driving for us. Somehow we came back to him (Sorokin) and things started to work better for us. Maybe we got the car running better, maybe he got better but I feel like we all kind of evolved together.”

For Sorokin, this was nirvana indeed. His ambition was to be a professional dragster driver and here was an opportunity to hammer the throttle, kick out the jams—and get paid. Notoriously hyperactive and quick as an outhouse mouse on the Xmas tree, Sorokin was a fearless capsule monkey who thrived on going into orbit no matter how sketchy the conditions on the launch pad. Sorokin had Go! Fever as bad as any Southern California boy, and he was willing to get himself strapped into a nitro-burning rattletrap rocket no matter what the circumstances.

“He was so damn good at what he did. And all he wanted to do was win,” remembers Jobe. “He wasn’t interested in arguing about the nuts and bolts, ‘that’s your problem;’ he didn’t even care.”

With the triumvirate simpatico, and Sorokin dependent upon win lights for his rent and lunch money, The Surfers arched more than a few eyebrows amongst their contemporaries and competitors with their fashion sensibilities, their engineering prowess and an uncanny knack for racking up Top Eliminator trophies. This unnerved the competition—a couple of Surf City hodads were killing ‘em at Drag City—but it thrilled the railbirds and it gave the media a human-interest “hook” to ratchet up their race reports. The whole “surf” thing, however, was a ruse…

“None of those guys surfed,” remembers Hier. “None of ‘em had a board.”

Sorokin tried to keep the image of beach bums in perspective. “Surfing kind of scares me,” he confessed rather dryly to Drag World. But his droll backpedaling was too late. The die had been cast.

Jobe, musing on The Surfers’ sartorial ensemble of Pendeltons, deck shoes and skateboards, says, “They didn’t know what to think of us, we were thought of as just… this was before hippies… but we were thought of as just some long-haired freaks from the beach.”

“They were definitely different,” recollects Roland Leong, nowadays the pit boss on Don Prudhomme’s Funny Car but then proprietor of the infamous Hawaiian AA/Fuel Dragster that claimed Top Fuel Eliminator at the ‘65 and ‘66 Winternationals. “I remember seeing these guys at Fontana and Bakersfield and they pulled in there with an open trailer with a ‘55 Chevrolet and uhh, like uhh, ‘Who are these guys?’ They called themselves ‘The Surfers,’ right? And me, coming from Hawaii, that wasn’t my idea of a surfer, you know what I mean? I guess in California terms they looked ‘beach’ kinda’ guys, but in my eyes…

“When you think about it, at the time we were all young and the word ‘nerds’ wasn’t in our vocabulary,” Leong adds. “But looking back, they looked like the intellectual-type as opposed to some greasy drag racers, which is what we were all known for at the time.”

Regarding the perception of The Surfers as beach-bum misfits and geeky oddballs, Skinner—who now answers to the name “Roberto”—was oblivious. He says, “Some people live their lives and other people live their lives but at the same time it’s like they’re standing off at a distance and watching themselves. I’ve never been that observer.”

Skinner maintains there was no contrived image, but others theorize that the persona of beach buffoons with sand-in-their-snorkels was a calculated, theatrical red herring. But archrival Leong saw through the skullduggery of the Surf City minstrel show. “All of ‘em were pretty smart guys,” he says. “With the budget they had to run on, they did an excellent job. They didn’t have the funds, so a lot of their stuff they had to make or spend their money very wisely. They didn’t have a lot of what we call perks, you know what I mean?”

“It wasn’t very long before they were pretty dialed in,” Hunnicutt corroborates.

Indeed, soon the drag-strip world was talking about the beatniks from the bay, not out of bemusement but out of respect. It was obvious The Surfers were onto something… Just ask the denizens and the vanquished dragster drivers of San Fernando, Long Beach, Fontana Drag City, Riverside, Bakersfield, Irwindale, Pomona, Fremont, Amarillo, Salt Lake City, Pocatello, Union Grove, Rockford, Maple Grove, Atco, and Denver. At every one of these venues, The Surfers either bagged Top Eliminator, recorded Low Elapsed Time or turned Top Speed of the Meet—and sometimes all three. (In Amarillo, they won two match races on the same day. Roland Leong’s Hawaiian AA/FD was bongoed in a towing accident so the track manager enjoined The Surfers to go best-two-out-of-three against local hitters Eddie Hill and Vance Hunt… the Californians swept both matches.) They were no longer geeky gremmies. They were Heroes.

*********

To: Joe Buysee, Lansing Michigan From: Mike Sorokin, Mar Vista, CA

Hi Joe,

Thanks for the nice letter. I’m glad we didn’t disappoint you at Bakersfield. It’s fans like you that make our efforts worthwhile.

I’m sending you a t-shirt. It’s used, but clean. I’m sorry I have to send you a used one, but there are no new ones around. I don’t think we will be in the Michigan area this year, but maybe next season.

Sincerely,

Mike Sorokin & The Surfers

*********

The wave continued its crest. Skinner asserts that, “At that point in life I would say that we were totally focused on our deal.” In a separate conversation, Tom Jobe agreed and then elaborated on their approach to conquering Top Fuel. “We went at it in a very conventional fashion,” he said. “All the guys that had the goofy combinations were never gonna do it… (and) if you had a mainstream deal you couldn’t get banned. We had a very clear view of that. ‘We’ve got to attack this from a mainstream angle.’ That way your advantage is invisible.”

Ron Hier explains one example of their focus and aversion to “goofy combinations” was to remove parts they considered superfluous. “They never had run an idler belt on their blower,” he mused, “because Tom Jobe felt that it was just another accessory that they might have a problem with, something else that could break. So when they put the motor together and they wanted to change belts, they would unbolt the blower and tilt it forward until the pulley was underneath the belt and then push it down onto the manifold and bolt it down. All during the time they were running that car, they never lost a blower belt.”

On the absence of the idler pulley, Skinner is nonplussed. “We figured we could just get along without it, so why have it if you don’t need it?”

*********

Hi Joe,

What’s happening? Not too much going on around here. We’re building a covered trailer for our tour and we don’t have much time for racing at the present time. Our race with the Goose will be our last local race.

Our car isn’t exactly beautiful, but it IS functional. Beauty doesn’t always get the job done. We are building a new car which should be pretty nice looking. Full body and all that trick stuff.

Well, maybe I’ll see you pretty soon.

Mike

*********

In 1966, Roland Leong’s engine czar Keith Black went on record in Hot Rod Magazine as defining a 75% nitromethane mixture as “heavy.” Ergo, 100% was not just volatile—it was certifiably insane. Of course, this was the percentage that Skinner and Jobe considered ideal for their tune-up. To the mighty Surfers, cutting the nitromethane with alcohol was even more absurd and non-linear than using a blower pulley. More is good, too much is better, right? But were these yin and yang yahoo alchemists pushing the envelope of internal combustion beyond its tension threshold? Were The Surfers off their trolley? Had they gone too far? On the contrary: At this moment The Surfers were the manifestation of a phenomenon that happens in physics all the time: When envelopes are pushed, the parallel lines of, say, method and madness, bend and distort, and at some point they are no longer parallel, at some point they actually intersect. Method and madness become the same thing… Madness becomes rational. The Surfers had reached that lucid intersection.

Ron Hier depicts “the lunacy” of Skinner and Jobe’s fuel mixture: “They originally started at about 50% nitro but Jobe didn’t like the (lack of) accuracy of the hydrometers. He thought they were a bunch of crap because they couldn’t get the right mixture on them; you were never sure what it really was, so he said, ‘If you just pour it out of the can we could eliminate that (uncertainty).’ That was Jobe: Eliminate all the mistakes. So instead of mixing it and getting a bad mix he said, ‘We’ll run a 100%.’”

Another theory was that the beakers were too expensive for The Surfers’ budget. Ironically, this is a rumor that Skinner and Jobe started themselves. It was really quite unnerving to see Sorokin gleefully pouring pure, undiluted nitromethane into the tank—all because his team couldn’t afford any more beakers. Skinner expounds on the “no hydrometers” rule this way, “What we used to say was that we didn’t want to break the hydrometer, but basically what we were trying to do was get as much energy out of the fuel as possible. Our game plan was about efficiency… to try and maximize the potential power that was available in the fuel. It took a long time to do that.”

So what was the percentage? “100%,” he answered. “Well not 100% but close… we had some stuff we put in there, y’know? We had some additives that took some percentage, something anybody could buy to stabilize things a little bit… in the neighborhood of 1 or 2%.”

Jobe concurs about the percentage, but adds that the decision to run this outrageous percentage was strategic on a variety of levels; most importantly, it shrewdly negated The Surfers from falling prey to their own pranksterish tactics. “Since most of those guys could add nitro and kill their motors—we couldn’t add any more because we already had the whole thing, right? We had it planned that you couldn’t destroy the thing almost no matter what you did. The other guys would typically run 70 to 80% nitro and if you could get them panicked they would add another 5 or 10% and blow the thing up.”

Yep… Despite their public image as oddballs who ran 100% nitromethane because all their hydrometers were broken, an image they helped cultivate themselves, in reality this cagey alchemy was another trump card for these wiseacre college kids from Santa Monica. It was a pearl of wisdom they had gleaned from their academic studies…

“I was going to college—mechanical engineering—and I just set about studying nitromethane,” explained Jobe about what led to a witch’s brew of pure nitromethane. “I would get the head of the chemistry department or whoever and get them all involved in what we were doing—and they’d cop a plea right away and say, ‘Hey, I don’t know how to do anything really, I’m just a teacher’—then they’d find out what we were talking about was going to get drug out to the starting line on Saturday night…So I’d say, ‘Hey, you’ve got to keep me straight on the theory, I want to make sure I don’t start deciding that gravity pulls from the side and get screwed up out there,’” he rhapsodized.

“So I set about studying how nitromethane worked,” he continued. “The reactions, both when you burn it and when you detonate it and how they differ; what causes it to detonate versus burn; what attitudes increase or decrease the tendency to detonate. At that time there was a lot of literature out because there had been some train-car explosions and other unexplained explosions that happened with nitro so a lot of research had been done where they dropped 55-gallons drums of the stuff from towers and shot it with 50-caliber machine guns trying to figure out how these tank cars went up in, I think, Illinois.

“That was the basis of what made our deal run good,” Jobe determined, “figuring out the nitro angle of it. And then figuring out how many BTUs were in 60%, 70%, 80%… Also,” he proffered, “I was old enough to where I had watched the transition from gasoline to alcohol at the drag strip; when I was, say, ten years old I was watching ‘em put together alcohol and gasoline—which don’t mix, right?—so at the starting line one of the crew would come up and grab the frame of the dragster and start shaking it to mix the stuff up, and I’m watching this as a little kid and going, ‘Man that’s stupid. If alcohol is good, why not just throw the gasoline away and go with the alcohol?’”

Remove all obstacles in the path, eh?

“When we did our deal we were going, ‘Why use alcohol? Let’s just throw that shit away. That stuff doesn’t make it go… It’s just pollution.’”

Jobe’s old man was a jeweler and his workshop became The Surfers’ impromptu research and development laboratory. “We continued our experiments at my dad’s factory in Santa Monica,” he says. “He had some jeweler’s lathes that we used to make all kinds of goofy nozzles. Do you remember in Science Class, Bernoulli’s equation? That defines all the stuff you need to know to make a nozzle… Anyway, we made ‘em look just like the pictures in the science book.”

The “Kinetic-Molecular Theory of Gasses According to Jobe” is indeed the crucial element to The Surfers’ success. Beyond that, it is also a blueprint on the mechanics of running a Top Fuel dragster—thirty years later. Outrageous nitro percentages, thin nozzles subjected to ludicrous amounts of pressure, and low compression are de rigueur for a contemporary fueler. But in ‘64, it was considered radical and suicidal. The Surfers debunked this as myth… by using a water faucet as a flow bench. Yes, a water faucet…

“We made us a flow bench out of a water faucet that had 60 lbs. (of pressure) which, at the time, was what most fuel injectors had. Ultimately, we made a whole fuel injector but then we found out that was stupid because then you don’t get any contingency money from Hilborn or whoever. Why throw away contingency money? So we just used Hilborn, but we made all the nozzles—we were into 200 lb. fuel pressure but we never told anybody. We had little tiny nozzles, but lots of ‘em, in order to atomize the stuff. You can’t burn liquid,” Jobe clarified.

“We found out that we could up the ignition’s amps, we could take fuel out of it.” Why less fuel volume? “All it’s doing is flattening your wallet. The more you atomize it, the less you have to put in to get the same amount of burnable, combustible stuff.”

The r&d at the jewelry workshop yielded a tangible, palpable difference between Skinner and Jobe’s digger and virtually every other machine at the race track: That is, the way it sounded. Tom Hunnicutt explains, “Their car sounded like no other car. You could tell when it was their car. If there were 100 Top Fuel cars and they all sounded the same, their car was completely off by itself. Their car was louder than anybody else’s and it had more fuel lines on it than anybody had ever seen.” Hunnicutt says about their swift conquest of the fueler wars: “They were kicking ass and not breaking anything. It was the perfect team.”

Skinner describes The Surfers’ mechanical ethos this way, “Efficiency, reliability was important to us,” he said. “Occasionally we had to take the head off or something. Occasionally we would break a roller tappet, occasionally we would lose a head gasket. When we ran the 64 cars at Bakersfield we didn’t have any problems.”

Because The Surfers were such a well-oiled machine and maintenance man-hours were minimal, this created ample opportunity for these free-thinkers to, uhhh, skateboard while the rest of the fueler guys were thrashing between rounds of competition.

“Skinner always had some skateboards to play with because we didn’t work on the car a lot like everybody else did,” Jobe says. To compensate for a lack of fiscal horsepower, the ingenuity of The Surfers manifested itself on the plane of psychological warfare; the boys occasionally deployed the skateboards as a weapon to combat their opponents’ deeper pockets and cubic dollars.

As Jobe tells it, “On the way to the drag strip we would talk about ‘What can we do to them today?’” he says. “‘What weird thing can we lay on ‘em?’ in ways they wouldn’t even figure out. We needed all the advantages we could get. A lot of the guys we had to compete against were well funded… The Lou Baneys and the Keith Blacks. All of those guys had really nice stuff. They had, like, new parts.”

Jobe remembers, “… a Sunday afternoon race at Fontana. All the bad guys from back East were gonna show up,” he says. “They were all puttin’ the mouth on us in the press saying what they were going to do to us West Coast guys. It was about an hour’s drive to Fontana from Santa Monica and we were talking and riding along and thinking, ‘What should we do today? Let’s not work on the car. We’ll come down and pick up the car at the other end and while Mike and his girlfriend pack the parachutes we’ll service the thing.’ We could service the whole thing in about five minutes. We said, ‘We’ll push right past the pits and we’ll put it right back in line and we’ll get out the skateboards and we’ll go torture ‘em in their pit area.’ So we did that—fortunately we didn’t break any lifters or anything,” Jobe remembers. “So we’d get the skateboards out. We’d go over and watch these guys (tear down) and we’d say, ‘Man, you guys sure are smart; you guys know how to work on these things and everything. Man, you guys are good!’ They didn’t know what to think of all that. By about the third round one of these East Coast hitters said, ‘Damn, don’t you guys ever work on that thing?’ We said, ‘N-o-o, we don’t work on it because we really don’t know that much about it. We’d just screw it up, it’s better just to leave it alone.’ And this guy is like, ‘(slowly) What-the-fuck-is-this-all-about?’ In the last round we got the mouthiest of the bunch, Bobby Vodnik, and we beat him and left ‘em all shaking their heads.

“Nobody ever found about the mind games, because we never talked about it,” he concludes.

*********

To: Joe Buysee, Lansing Michigan

From: Mike Sorokin, Mar Vista, CA

Hi Joe,

We will NOT be at Union Grove until June 25th. You can bet we will be trying to beat the Goose, we haven’t run the car for a month and I’m forgetting how to drive the darn thing. I hope your pal loses his buck. I think he will. We still have a few tricks to try.

I have been married for about a month. I like it.

We are not worried about the strip conditions. The car handles good and it has two chutes. We actually made No. 1 on the Drag Racing Magazine poll for the West. We were very happy about that. We are planning on running the US Nationals.

We didn’t get any color pictures in the article because our car isn’t pretty enough.

You don’t have to thank us. It’s a pleasure to meet fans like you. I just hope our future performance doesn’t let you down.

Well, I’ll see you later.

Mike

******

“Sorokin was a real high-strung kind of guy, very nervous,” says Tom Jobe. “He kept to himself and he loved to race.” On a typical Sunday morning, after rendezvousing at the Red Apple, The Surfers would stop for breakfast whilst en route to San Fernando Raceway. Once seated, Jobe describes Sork’s hyperactivity thusly: “Mike would be sitting there and he could not keep from bouncing his feet, jumping up and down and vibrating at the table.

“The guy was so high-strung that nobody could beat him at the starting line. And if you wanted him to be just a little bit quicker, you could just wind him up: You know, ‘Mike, so-and-so was saying that their driver could whip you’ and that would really make him vibrate. And if somebody actually pissed him off they could forget trying to beat him. I don’t know if he went into higher revolutions per minute or what, but he would really be quick,” Jobe remembers.

“He would just drive anything, but fortunately by the time we got rolling he was getting tired of all the coupes and roadsters and he wanted to drive something fast—and make some money too.”

The biggest test of Sorokin’s mettle transpired during the ‘65 UDRA meet at Fontana. During a semi-final heat the boys had blown the side out of the block. It was their only bullet in the entire inventory and until that moment, “it lived like Methuselah,” according to Sorokin. But rather than pack it in, our heroes improvised. They turned the car on its side, jammed the piston all the way to the top of the bore, removed the dead hole’s connecting rod, taped the crank journal and wrapped it with a hose clamp, taped cardboard (!) over the gouge on the inside of the block to keep from hemorrhaging oil and threw the pan back on. For the half-dead 392’s swan song, they dosed the remaining 7 cylinders on 99%, fired it up, and Sork staged the discordant, vibrating wounded machine like nothing was out of the ordinary. Despite the frenzied thrash, Sorokin expertly cut a gate-job that was sharp as a switchblade, and was scarfing up asphalt in a discombobulatory pell-mell fashion until the entire backfiring mill detonated and went kablooey at the top end. They lost the match, but won the respect of the entire drag-racing community with that gonzo, anarchic attempt to win a $1000 purse. Sorokin got more ink than the event winner…

“When we got done with one of those deals, Mike would just look at you like, ‘Is it time to go?’ and he’d hop right in knowing full well that the whole side of the motor is made out of cardboard and silver tape. There was a hose clamp around the crank where a rod used to be,” he concludes. “He didn’t give a shit. ‘Oh yeah, let’s go.’ He loved it.”

As The Surfers’ star continued to rise, Sorokin met Robyn Rains, a part-time trophy girl at the digs. “She is the best parachute packer I have,” said Mike, “and it’s nice to have a pretty girl to look at instead of all the racers.”

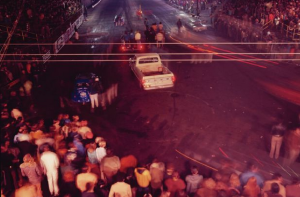

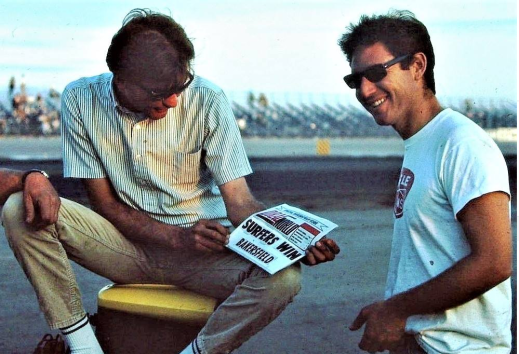

Robin packed the chute at all the races, including the ‘66 March Meet at Bakersfield, an event that has been described as “the purest drag race ever.” It was an absolute orgy, there were 102 AA/Fuel Dragsters entered in Top Fuel Eliminator that weekend. The Surfers outlasted ‘em all—and for punctuation they set a National E.T. record of 7.34 seconds.

Skinner reflects on Sorokin’s contributions to The Surfers’ triumph at Bakersfield like a calculus problem: “You can’t really pinpoint who does what,” he reckons, “but in order to win some drag races the car has to be running, the driver has to be able to not only get the thing down the track but leave at the right time. Plus, after a while he got to where he could control the throttle, where initially what he used to go was start the thing up and put the throttle down.

“I remember one thing that he said at Bakersfield. We ran the first round and ran a 7.40 and he said, ‘The track is really good, I think I can put the throttle down all the way on the next pass.’ And he wasn’t used to being able to do that. He definitely developed some finesse.”

But it was a culmination of elements, including all that r&d on the jeweler’s lathe. According to Skinner. “We worked a lot with our fuel injector—we evolved the fuel injector. Up until we won Bakersfield we never had a new blower. At Bakersfield we had a new/used blower. We were never on the cutting edge with expensive gadgetry.”

But The Surfers’ ken and karma transcended the limitations of their gear. It was their awareness that was “bleeding edge.” Intuitively, if not intellectually, The Surfers knew that matter and energy was interchangeable and both are keys given to humanity to open any door we seek. The Surfers chose the door to the Kingdom of Nitromethane, whose sacramental temple was in Bakersfield.

In the Winners Circle at Bakersfield, the paparazzi went bananas, with flashbulbs bursting like asteroids during the Big Bang itself. It was glorious, with the bespectacled Skinner mugging for the camera in the reflective light bouncing off the Miss Hurst Shifter Trophy Girl’s cleavage. Fame. Wealth. Top Eliminator. The Madcap Savants from Surf City put ‘em all on the trailer. And as stars shone on Kern County that night, as oil derricks teeter-tottered off in distance, the grunions were running at a motel in Bakersfield: Mike and Robyn Sorokin celebrated their triumphs in a cosmic sense and their son Adam was conceived. All across Creation, The Surfers were shooting the curl. Finally, they had achieved a spiritual duty greater than themselves.

But at their zenith, The Surfers encountered a fork in the road. Skinner and Jobe were burnt on drag racing and sought new challenges. “Skinner and I could see that the only guys who were ever going to make a living in this deal were the owner/driver/operator: the Prudhommes, the Garlits’s, the whatever,” said Jobe. “You could see that it was already headed in the direction. We worked a lot of hours,” he continued. “I went to school and had a part-time job and worked on the dragster. We were always just scraping by—and just barely. A lot of times we would show up to the drag strip with a crank that wasn’t even balanced…Mike wouldn’t be able to even see once he got halfway down the track the thing was vibrating so badly…He didn’t care, ‘Whatever…Let’s go.’

“We told Mike, ‘Hey, if you don’t think that you have to do this for the rest of your life, why don’t you look at it from the standpoint that we went out and did a bunch of wild shit, had a great time, kicked a lot of ass, took a lot of names and we’re all in one piece and we don’t have a nick on us. Let’s just forget about it.’ He said, ‘No, I think I want to keep going. I like doing this.’”

Skinner says, “We were really able to walk away.” Sorokin, however, was a different story. Sork was totally wired on driving a digger. Quitting the business wasn’t an option.

Sorokin reflected in the Santa Monica Evening Outlook on his perpetual yen to kick out the jams on the drag strip. “I spent two years at City College studying electronics because I thought it was the thing to do,” he said. “I found out this is what I wanted to do most. I think everybody has some kind of dream. This was mine and I’m living it. You can’t ask for much more.”

*********

Hi Joe,

How are things in the armed forces? Drag racing is getting rougher & rougher. We ran at Irwindale yesterday. It took a 7.57 sec. to qualify in a 16-car field. We broke in the third round after beating Gotelli-Safford and Tommy Allen. My writing is bad because I am holding my month old son, Adam. Very good-looking kid.

Anyway, in about a month, I think I will be driving the Hawaiian. The new car we were building when we quit racing is almost finished and it is without a doubt THE best looking car in drag racing. Richie Bandel, from Brooklyn, bought the car. We all hate to see it go. The old car is still for sale.

Well, G.I. Joe, take care of yourself and good luck.

Mike

*********

Sorokin’s next gig was driving for another titan of engineering, Ed Pink, which lasted for a couple of months. He then drove for Blake Hill for a month. Next, he got the call when Roland Leong decided to campaign two fuelers, one powered by a Chrysler 392 and the other sporting a newfangled 426-hemi powerplant. “Sorokin drove the 426 car,” recalls Leong, “and we won the Stardust meet in ‘67 at Vegas.” Keith Black was wrenching, Roland was cutting checks, and Sork was swapping pedals—a formidable collaboration on paper, but one that failed to set the world on fire in reality… It’s not like they stunk up the joint, they didn’t; it’s just that this combination just did not crush like Black, Leong and Sorokin were all used to. When Roland downsized to one fueler, he went with Mike Snively as the driver.

*********

Hi Joe,

How’s things in the Army? Good I hope. I was very happy to have won in Las Vegas. The win was badly needed.

It doesn’t take people very long to forget past accomplishments. I hope this won’t be the only big win. The cars around here are unbelievable. We ran 7.26 last week and didn’t qualify!

Keith Black is a pretty good guy to race with. He is plenty sharp. (My writing and spelling is terrible)

Well, goodbye for now, say hello to your mom.

Mike

*********

Reflecting on the trajectory of The Surfers’ endeavors, Skinner said, “It was kind of a curiosity, kind of an adventure to go on.” His reward was the process and not the goal… “I’ve taken a different path in my life than most people have,” Skinner said. “I’m interested in life-long learning and I’m trying to continually grow as a human being. My interests are much more spiritual and philosophical than trying to be famous or achieve something on a material level.”

For Skinner, his drag-strip endeavors were informative on an almost existential level. “I’m sure that having the success (we had) did something for my level of confidence,” he said. “It helped me realize that I could be independent and I could solve problems and solve them in a different way than the average person. I see myself struggling with…. structure.”

Ironically, drag racing hipped Skinner to the structure inherent in the symbiotic relationship that exists between humanity, technology and a given environment. “Tom is the person who masterminded our combination for the engine,” Skinner continues. “A lot of it really was kind of like a science experiment. It was nice recently that we were honored at the banquet for the Drag Racing Hall of Fame. I thought to myself, ‘What if someone asks me, ‘how did we do that?’ I’m not really sure, but I know on some level we made friends with all the parts and we had very intimate relationships with each of the parts. In order to do that, you have to be able to look at the part and on an abstract level. You have a conversation with the part. You look at the bearings and the bearing kind of talks to you and tells you what it needs so it won’t get hurt.”

*********

Hi Joe,

I was really saddened to hear about (name is illegible). He was a VERY nice guy.

I was layed off at work. They didn’t appreciate my taking two weeks off to go to Bristol.

We didn’t even qualify. A 7.35 in the first round was good enough, but a 7.40 in the second wasn’t. Plus the engine melted a couple of pistons. That engine is extremely temperamental. Only 6 days to the meet at Lions. I hope Black does the right thing and performs some of his miracles. He was talking about using an Enderle injector. That’s the only thing that hasn’t been changed in the engine.

Well, I’ll talk to you after the 15th.

Mike

*********

In the waning months of ‘67, Sorokin was back at the strip, shoeing a somewhat generic slingshot under the employ of Bakersfield racer, Tony Waters. In their three races together, they went out in the first round of competition each time. Sorokin and Paul Gommi, a fellow SoCal fueler freak, had ordered a new digger and they picked up the chassis on December 29th. The two of them looked forward to the holidays to blow over so they could get the car ready for the new season. “I talked to Mike the morning before we went to race in Orange County, see?” recalls Leong. “And what he did was he just picked up a brand new chassis from a guy in Colorado I guess, at the airport.”

This was the last race for Sorokin as a hired gun. With Gommi, he would now be owner/operator.

“He didn’t like the car he was driving, but that was a ride, right?” Roland says. “He was going to start putting together this brand new chassis, he bought the chassis with his own money and he wanted to know if I had some parts that he might need to finish the car up. I said, ‘Yeah, we’ll talk about it. Then he asked me if I would be home Sunday…” Leong pauses when he remembers the weekend of December 30th, 1967 when the flaws in the clutch technology were showcased in a most grisly manner.

As Morton alluded to in The Stainless Steel Carrot, clutches had a tendency to pull the bolts out. After a few laps under maximum torque, the asbestos disks would periodically shred apart and would create a domino effect throughout the bellhousing. Ultimately, the flywheels cut through the aluminum bellhousing and the chrome-moly chassis like a buzzsaw through Brylcreem. This was one of those nights.

Tom Hunnicutt was sitting in the bleachers with Jim Boyd during the first round of eliminations. “Sorokin left the line and got about halfway down and I remember this horrendous metal sound. I remember looking straight down (from the bleachers) and as he went by, I remember seeing the light off of the top part of his helmet,” recalls Hunnicutt. “The rear wheels had stopped—this was at 220 (mph) or whatever—and the front part of the car was gone.” At this point the bolts sheared and the flywheel cut the chassis completely in two. Worse yet, the rear end seized and was freewheeling inside the rollcage at 218 mph. This forced Mike out of the cockpit. “He was half out of the rollbar. I thought to myself, ‘Maybe he’s trying to get away from it… why is he standing up?’ About that time the tubes dug in and he started tumbling. And every time it went over, it was like a rag sticking out of a ball all the way down the drag strip, all the way to the end… It was the worst thing I have ever seen.”

After the horror and the screaming and the god-awful grinding subsided, there was silence. Everyone on the premises was stunned. Some folks were literally in shock.

“We walked back to the pits,” Hunnicutt continues, “and I remember Frank Pedregon was putting his car back on the trailer—and he was in, he was qualified. Jimmy was in denial and kept asking him, ‘What hospital are they going to take him to? Maybe we can go see him.’ Frank finally had to tell him, ‘Jimmy, he doesn’t need a hospital.’ It was one of those things you don’t forget for your whole life.”

“Anyway, even in the staging lanes I talked to him a little bit about it (getting together on Sunday).” Roland recollected. “I guess as long as I’ve been doing this, I’ve kinda seen it all so to speak…But it’s kind of an eerie feeling to just talk to a guy before he gets pushed down and the next time you turn around he’s dead.”

Once again, the universe shuddered because of Mike Sorokin. But this time it was from his passing. Sorokin’s son was a year old. He vaguely recalls the phone ringing and hearing his mom screaming when she was given the news. It was perhaps drag racing’s darkest moment, and at the very least, an ugly punctuation to the legacy of The Surfers.

*********

April 11, 1968.

From: Roxanne Gibson (Note: Mike Sorokin’s sister-in-law)

To: Pvt. Joe Buysee

Dear Joe:

I just finished reading your letter, it’s so sweet and thoughtful of you to find time to write me, I know how hard it is to keep up with your letter writing. I don’t know how you do it.

Joe, I just feel sick inside about all that goes on over there. I wish like crazy you American guys didn’t have to be over there. I also received today a letter from our gal Robyn. She’s fine and Adam too. They left for Spain April 7th.

That’s too much about your license plate, my birthday is April 18th, so I’ll be thinking about, “Roadrunner” except I’ll be 28…wow, 27 years older than your car.

So long for now, Joe.

Roxanne

(Pvt. Joe Buysee died of a rare brain disease in December, 1970. Depending on whether you ask his family or the government, it may or may not have been related to exposure to exotic, strategic chemicals during his tour of duty in Southeast Asia.)

*********

And The Surfers were this: They took the promise of America, tipped it over, and ran it out the back door. They chose their moment, took the trappings of our American Dream and manipulated it to their own ends, baby. And then they moved on because everything is ephemeral in the universal scheme of things, a theorem proved by Sork’s shocking and profound passing. The memory of The Surfers and their exploits, however, continues to influence and affect everybody who was touched by their presence and anybody who saw them run.

In March of 1997, The Surfers were inducted into the Drag Racing Hall of Fame. Skinner didn’t even know it existed. He showed up at a black-tie affair in striped two-tone red pants, a flannel shirt and a Panama hat. Jobe was equally perplexed. Ron Hier relates the following anecdote from the ceremony: “Like Jobe said, ‘We did it and that was that—and now I’m in the Hall of Fame, I can’t fathom it, how did this happen?’ So I told him, ‘You gotta look into it a little more and understand what happened to drag racing after you left.’”

But Jobe is nothing if not a crisp, clairvoyant thinker and he knows the perfect wave is rare, indeed. He saw that the parameters and the scope of drag racing would be narrowed into a diameter thinner than his own fuel nozzles, that the scope of something defined as unlimited would narrow into something quite finite. “Rules create a funnel,” Jobe explained in very matter-of-fact tones, “and at the end this just creates red dragsters and green ones and blue ones.” He continues to describe the inevitability of homogenization. “Rules end up defining the vehicle: The wheel base, the height, the width. The only thing left is the color,” he said, “and that is taken care of by the sponsor. That’s evolution.” One hundred percent.

(Originally published 1998)